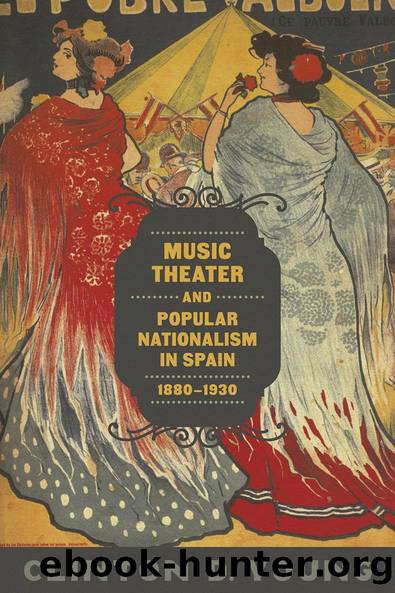

Music Theater and Popular Nationalism in Spain, 1880-1930 by Clinton D. Young

Author:Clinton D. Young [Young, Clinton D.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: History, Europe, Western, Spain & Portugal, Music, General

ISBN: 9780807161050

Google: fhMuCwAAQBAJ

Publisher: LSU Press

Published: 2016-01-11T02:58:47+00:00

6

Zarzuela and the Operatic Tradition

When the influenza pandemic of 1918 reached Spain in the autumn of that year, the hit zarzuela playing in Madrid was La canción del olvido (The Song of Oblivion), which featured a number that had already become popular outside the show: the song âSoldado de Nápolesâ (The Soldier from Naples), which rapidly became the Spanish nickname for the so-called Spanish Flu. The libretto by Federico Romero and Guillermo Fernández-Shaw manages to infuse freshness into a stock situationâthe rake who is redeemed through the love of a good woman, and their sure sense of stagecraft contributed to the success of La canción. But in all musical theater pieces, it is the music that is responsible for the ultimate success or failure of the work, and the score to La canción would be the finest ever written by José Serrano. (Fernández-Shaw would later compliment the score by joking that the reason the influenza became known as the âSoldado de Nápolesâ stemmed from the fact that both were equally contagious.)1 Serranoâs score is notable not only for its rapturous melodies and keen theatrical sense, but also for the way it manages to sum up the zarzuela music of the previous decade. It incorporates the sound of European operetta that composers had begun to cultivate during the 1910s, and it incorporates musical tropes from yet another genre that Spanish composers had been using during that decadeâopera.

The operetta element to La canción del olvido is the most obvious facet of the score. Many of the numbers, notably the title song (No. 2 in the vocal score), require trained voices and are orchestrated heavily for strings and harp. Although some critics have found these numbers (especially those of leading lady Rosina, of which âLa canción del olvidoâ is one) to be more operatic than operetta-derived, the vocal lines are more restricted in tessitura than one would expect to find in Italian opera.2 The specifically Spanish and zarzuela-driven elements can be found in the choral numbers, which follow the zarzuela tradition of having the chorus represent a segment of the population (albeit here of Naples rather than of Spain). This is made clear by the fact that the chorus is always accompanied by a group of street musicians known as the rondalla, rather than by the orchestra. The guitar and lute accompaniment of the rondalla were clearly meant to evoke the street musicians who had helped to popularize zarzuela music in Spain, without necessarily losing the Neapolitan atmosphere that Serrano, Romero, and Fernández-Shaw were attempting to re-create. (The use of the rondalla is no doubt meant to recall the use of street musicians in the scores to works like Pan y toros, El barberillo de Lavapiés, and La verbena de la paloma. It also foreshadows similar treatments in Doña Francisquita, La Calesera, and La parranda.) In addition, the choral numbers tend to comment on the action, especially the central choral number and the most famous piece of music from the zarzuela, the âSoldado de Nápoles.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11798)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8961)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(5171)

Paper Towns by Green John(5168)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5067)

Industrial Automation from Scratch: A hands-on guide to using sensors, actuators, PLCs, HMIs, and SCADA to automate industrial processes by Olushola Akande(5042)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4287)

Be in a Treehouse by Pete Nelson(4028)

Never by Ken Follett(3924)

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3838)

Goodbye Paradise(3794)

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro(3387)

Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer(3375)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3361)

The Cellar by Natasha Preston(3327)

The Genius of Japanese Carpentry by Azby Brown(3281)

120 Days of Sodom by Marquis de Sade(3253)

Reminders of Him: A Novel by Colleen Hoover(3067)

Drawing Shortcuts: Developing Quick Drawing Skills Using Today's Technology by Leggitt Jim(3063)